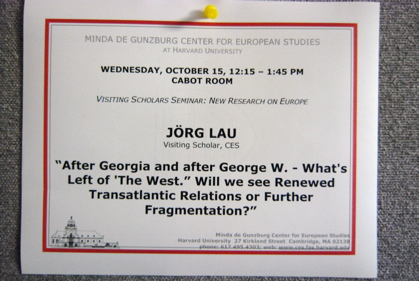

Im folgenden mein Vortrag in Harvard am Center for European Studies:

There is a warning sign at french railway crossings. It reads: Attention! An incoming train can hide another one! „Attention! Un train peut en cacher un autre!“

I should have remembered this while choosing the title for this talk. But no. Instead I went for the obvious pun about Georgia and George W. That seems a little outdated today. Because that’s what happened in the last 6 weeks: While looking out for one train, we were hit by a second one.

I should have remembered this warning while choosing the title. But no. Instead I went for the obvious pun about Georgia and George W. That seems a little outdated today.

Because that’s what happened in the last 6 weeks:

While looking out for one train, we were hit by a second one.

Who cares about Georgia these days? What happened to what seemed to be the most serious crisis since the Iraq war?

Looking back after three weeks of economic turmoil, the Georgian conflict almost looks dwarfed in relation to the worries that we are now facing.

This fact is very telling in itself: It speaks to the situation of the EU and the US that a conflict that seemed to remind of the Cold War has been overshadowed by a crisis of a completely different order. Let’s put it this way: The West’s room for action in the Georgian crisis will be determined by the outcome of the financial crisis. The „financial crisis“ is much more than this wording suggests. I will adress this later in the talk.

Anyhow, I am here at CES to try and find out which way transatlantic relations could go after these eight years. Are we going to see a more divided and more fragmented west in an increasingly multipolar world? Or are we going to see a resurgence of power block politics under a new headline – liberal democracies vis à vis autocratic regimes? A little bit later I will briefly discuss two major publications dealing with this alternative.

Where do we stand in transatlantic relations at this very moment? I would like to play time machine with you and go back more than five years to a very significant moment.

It is the eve of the Iraq war.

The American president is on his ranch in Crawford Texas, like so many times during his term. He is entertaining an important ally from Europe – the conservative Prime Minister of Spain, José Maria Aznar. Aznar is willing to change the course of Spanish foreign policy according to the wishes of the Bush White House. For the first time in modern Spanish history, the country is going to be a part of an invading alliance – side by side with the United States. It’s no small thing for the Spaniards to do this. A huge step actually, a very daring political bet for Aznar.

It would kill him politically eventually. Here is a man who was even willing to split the EU for this very gamble. You might think he was expecting a little empathy from his counterpart.

But the American president seems very much unimpressed.

By historical coincidence we have obtained the protocol of the talks in Crawford. This is a unique document.

I though it might be fun to read the most outrageous passages to you. So let me just try to transport you to Texas for some minutes: Aznar keeps begging Bush to help him with the public at home. The Spanish are not fond of the war plan. Bush keeps talking about his fantastic schemes.

„We can win without destruction“, he says.

He already has plans to transform Iraq into a federation. „Meanwhile“, he says, „we’re doing all we can to attend to the political needs of our friends and allies.“

PMA (Aznar): We need your help with our public opinion.

PB: We’ll do everything we can. On Wednesday I’ll talk about the situation in the Middle East, and propose a new peace framework that you know, and about the weapons of mass destruction, the benefits of a free society, and I’ll place the history of Iraq in a wider context. Maybe that’s of help to you.

PMA: What we are doing is a very profound change for Spain and the Spaniards. We’re changing the politics that the country has followed over the last two hundred years.

PB: I am just as much guided by a historic sense of responsibility as you are. When some years from now History judges us, I don’t want people to ask themselves why Bush, or Aznar, or Blair didn’t face their responsibilities. In the end, what people want is to enjoy freedom. …

PMA: The only thing that worries me about you is your optimism.

PB: I am an optimist, because I believe that I’m right. I’m at peace with myself. It’s up to us to face a serious threat to peace. It annoys me to no end to contemplate the insensitivity of the Europeans toward the suffering Saddam Hussein inflicts on the Iraqis. Perhaps because he’s dark, far away, and a Muslim, many Europeans think that everything is fine with him… The more the Europeans attack me, the stronger I am in the United States.“

This was 5 and a half years ago, in the run-up to the war that is still going on.

The transcript of Bush’s meeting with Aznar would make a terrific theatre play: on the one side the increasingly impatient young Emperor, longing for action, yearning to send his troops into battle – on the other side the experienced old diplomat, a bit cynical from all the things he saw in his life, trying to gain time by pointing to the needs of the allies.

„The only thing that worries me about you is your optimism“ – Aznar’s skeptical remark is a sentence that sticks with you.

Bushs response would make a great headline for his chapter in the history books:

„I am an optimist, because I believe that I’m right. I’m at peace with myself.“

And then, there is the core sentence about US-European relations in the Bush era: „The more the Europeans attack me, the stronger I am in the United States.“

Does this logic still work? I don’t think so. This is over, too.

But still: The McCain-Camp tried to make use of this logic during their summer troubles.

Senator McCain was falling behind in the polls – and he had problems getting media coverage during Barack Obama’s world tour.

When Barack Obama spoke to an enormous and enthusiastic crowd of 200.000 in Berlin, Senator McCain’s staff came out with a tv ad claiming the turnout in Berlin was due to Obama’s celebrity status: A european celebrity, that is.

The more the Europeans like Obama – such was the logic of this ad – the better for John McCain. Did it work? Only for a little while. There was a short spike in McCains polling numbers after the ad was published.

But all this was swept away when the second train – the financial crisis – came around the bend.

Let’s look for a moment at these two events – Aznar in Crawford – Obama in Berlin – because they show how things have changed dramatically in the last several years.

These two moments are like metaphors for two very different paradigms of transatlantic relations. On the one hand there is the leader of the western world summoning an ally to his reclusive Ranch, pushing him around like a subservient client – the whole scene somewhat reminding of the Godfather, Part I.

On the other hand you have a candidate who includes the Europeans in his campaign – obviously ignoring the received wisdom that this might hurt him (which it actually did for a short time).

And by the way, what Obama said in Berlin was quite remarkable. I quote:

„The fall of the Berlin Wall brought new hope. But that very closeness has given rise to new dangers – dangers that cannot be contained within the borders of a country or by the distance of an ocean. (Like Terrorism, financial crises, viruses ect.)

(…) None of us can deny these threats, or escape responsibility in meeting them. Yet, in the absence of Soviet tanks and a terrible wall, it has become easy to forget this truth. And if we’re honest with each other, we know that sometimes, on both sides of the Atlantic, we have drifted apart, and forgotten our shared destiny.

In Europe, the view that America is part of what has gone wrong in our world, rather than a force to help make it right, has become all too common. In America, there are voices that deride and deny the importance of Europe’s role in our security and our future. Both views miss the truth …

Yes, there have been differences between America and Europe. No doubt, there will be differences in the future. But the burdens of global citizenship continue to bind us together. A change of leadership in Washington will not lift this burden. In this new century, Americans and Europeans alike will be required to do more – not less. Partnership and cooperation among nations is not a choice; it is the one way, the only way, to protect our common security and advance our common humanity.“

Within all the warm rhetoric of bridging the atlantic gap there is a sober warning here: The burdens will not be lifted by a change of leadership in Washington! Obama was in fact telling the crowd in Berlin that a renewed partnership would not mean holding hands and singing Kumbaya (as the american saying goes). But rather that both sides would have to do more. I doubt that the enthusiastic crowd picked up this message – but Obama cannot be blamed of hiding the truth from the Europeans.

Here is my take:

With a President Obama, some things would get tougher for the Europeans, especially the Germans. His deal with the American people in foreign affairs is: I will close the gap between us and the rest of the world, that the Bushies have widened to a canyon.

This will entail a new balance when it comes to burden-sharing. The tacit agreement not to press each other over Iraq and Afghanistan will be overruled by the sheer necessities. Obama says he wants to end the wrong war (Iraq) and win the right one (Afghanistan). So he will need to show that he can rally the world behind this. And for the Germans it will be very hard to say No to anything he asks for, exactly because they had this tacit agreement with the Bush administration while at the same time criticizing them. You can hardly say No to a president who is on the same page with you on Iraq and Afghanistan.

But at the same time the domestic pressure to withdraw our troops will become stronger: We too have an election coming up in Germany!

Here is a possible scenario: A more multilateral-minded American president putting pressure on the allies to engage more, while they come under increasing domestic pressure to beginn withdrawing.

Let’s take a step back to see the broader picture:

We are witnessing a major power shift in international relations. And it seems a historical irony that this should happen in the sunset of the Bush presidency. George W. Bush, the man who is – or used to be ? – „at peace with himself“, is presiding over an unprecedented loss of american standing in the world – diplomatically, geostrategically and economically.

Let me quote a recent survey by the German Marshall Fund of the United States, conducted in the US and 12 European countries.

In 2002, 64% of Europeans viewed US leadership in world affairs as desirable, and 31 % as undesirable.

In 2008, a mere 36 % of Europeans viewed US leadership as desirable, whereas 59 % saw it as undesirable.

The steepest declines among countries surveyed since 2002 were found – where? – you never guess! – in pro-american Poland, where the numbers fell from 64 % in 2002 to 34 % in 2008. Germany comes in second, the numbers declined from 68 % in 2002 to 39 % in 2008.

Obamas high favorability ratings mirror these ever declining numbers: The highest ratings for Obama were found in France: 85% there would prefer him over his opponent, in the Netherlands 85% and in Germany 83 %.

47 % of Europeans believe relations will improve with a President Obama, 29 % believe they will stay the same, and 5 % think they will get worse.

Compare this to Senator McCains numbers: 11 % believe the relationship will get better, 49 % think it will stay the same, and 13 % think it will get worse.

These are significant numbers. I cannot present hard evidence here, but from many interviews I conducted for my reporting about foreign policy I can assure you that the political class of Europe thinks along the same lines. The interesting thing: This is not a partisan issue. Ask conservative members of parliament in Germany or France about their preferences, and you will get an overwhelming vote for Obama (off the record, of course). Even those who have sympathized with George Bush in his first term are utterly disillusioned: „After all these years, we need someone we can work with, someone who listens and consults.“

You can hear this on both sides of the aisle. A leading conservative member of the Bundestag’s foreign affairs comittee was quoted as follows during George Bush’s farewell tour last summer: „We will not miss him.“

In a final ironic twist, George W. Bush has now become the undertaker of the most powerful financial system in human history. Surely the mortgage crisis, the credit crisis, the de facto nationalisation of major banks and the ensuing demise of Wall Street all happened on his watch – this strikes a devastating blow to his economic philosophy of deregulation and self healing power of the market.

What happened in the financial arena is obviously not a containable incident. It will also have wide ranging effects on american foreign policy.

Wether or not the administration’s rescue plan succeeds, foreign perceptions of America’s financial folly are bound to diminish America’s standing in the world.

The Bush plan to cure America’s financial ills is seen by non-western countries as a display of hypocrisy. When their economies encountered crises, poor countries in Africa and Latin America were instructed by US officials and advisors to avoid government intervention and allow market forces to work their cure. The populations had to suffer through debilitating recessions before they could hope to attract credit from abroad and foreign investment.

Today, the same US administration that vehemently stood up for the inviolability of free markets elsewhere is intervening in the private sector – and on a scale those foreign onlookers could only dream about. Maybe you have read trhe story in today’s Times: Henry Paulson invited the senior manager of the american banks over to the treasury, and then he made them an offer they couldn’t refuse – to buy shares of their banks, effectively partly nationalising them. The bankers, desperate for capital, all signed up.

Interestingly, Paulson’s move followed the European strategy of dealing with the credit crisis: injecting capital directly into the banking system instead of buying up the bad assets.

This seeming double standard of preaching water to the rest of the world, but drinking wine at home will haunt not only the US, but also the Europeans, who have been forced to act against their own fundamental economic tenets of deficit control, fiscal stability and free markets.

We are witnessing among other stupendous things the end of the so called „Washington Consensus“ – the 10 point recovery package that was designed to help ailing economies in the developing world. The Washington consensus‘most prominent important recommendations were privatization of state enterprises and abolition of regulations that impede market entry or restrict competition, in short: deregulation.

Another irony there: It was not criticism from the outside that killed the so called „neoliberal agenda“. This time, it’s not Venezuela’s Hugo Chavez or Brazil’s Lula da Silva, who are railing against globalisation.

No. The Washington Consensus was killed in Washington by Washington. You might aks yourself: What in the world is left for Noam Chomsky to do now?

It is not a risky guess to say that we will see even more nationalisation of private enterprises in the years ahead – especially in financial sector, and more and more regulation and banking oversight. But this is not my issue here. Let’s look at the broader impact: The current financial cyclone is having an effect not only on the economic philosophies American experts have been writing for the rest of the world, but also on US national security.

There are signs that managers of sovereign wealth funds in China and the petro-states of the Arab world are losing confidence in the resilience of the American economy.

After investing more than $8 billion last year in the private equity group Blackstone and in Morgan Stanley, the China Investment Corp. has seen the value of those stakes drop by 43 percent.

Loss of confidence in the American economy could bring nasty consequences not merely for the dollar, but also for the conduct of US foreign policy.

This is a quite remarkable aspect of the events which has not been taken into account as much as it should be. A reporter for my paper in Beijing was able to reconstruct the role the Chinese authorities played in the undoing of the american financial sector.

It started with a significant pullout by the Chinese Central Bank of their Fannie and Freddie assets. These amounted to 376 billion dollars. Between July and September the Chinese got rid of 23 billion dollars worth of credits they had given to the US firms. During the Olympics, they urged President Bush to take the institutions into federal hands. When he failed to act immediately, a Chinese official sent an email to Bloomberg financial newswires: „Should the Us government let Freddie and Fanny die and leave international investors without compensation, there will be catastrophic consequences. It will be the end of the current international finance sytem.“ This was on August 22nd. One week later, Bank of China announced it had reduced its investment with Fannie and Freddie about a quarter.

They were basically threatening to stop lending money to the US. Even if this was a bluff, it worked.

Another week later, Fannie and Freddie were under temporary government oversight.

In their own view, the Chinese had prompted the US to intervene into the mortgage market and guarantee a large part of bad credits to protect the international lenders.

Whatever the actual part of the Chinese in the story may be – the perception of their considerable influence will definitely change their attitude on the global stage. A chinese official told an FT reporter last week: „America drowned itself in Asian liquidity.“

And here is what Niall Ferguson suggests we should hope for to ward off a remake of the Great Depression: „But while we certainly face a global slowdown, we may yet avoid another depression. Finally, the possibility still exists (…) that the Asian and Middle Eastern sovereign wealth funds could step in to recapitalize U.S. and European banks before they succumb to another great contraction.“

Again a remarkable reversal: Can you remember the hysterical debate only two years ago in this country about a Middle Eastern investor from Dubai wanting to buy up American ports services? The investor was eventually discouraged and sold all his assets, because it seemed too risky in the face of public animosity. But look where we stand now: Instead of scaring these investors away because of security concerns – we are now hoping they might want to buy our flailing banks!

Add to that what happened to the once proud Icelanders last week: After facing bankruptcy from the involvement of Iceland’s banks in the international credit crunch, the government of Prime Minister Geir Haarde first nationalised the two biggest banks. And then he had to ask Vladimir Putin of Russia for a 4 bn € loan to keep the country afloat.

These are just some examples to make my point: Living up to the longterm geopolitical implications of the current crisis will be equally painful for the rich nations as paying the domestic price.

The current crisis, though a financial one, feeds into the political crisis brought about by the Bush administration: The erosion of the west’s moral authority – that began with the Iraq war – has been greatly accelerated. The newly dependent west cannot any longer expect its creditors to listen to its lectures. And here lies the broader lesson:

For years now, we have heard of the shift eastwards ans southwards in global economic power. It is almost a commonplace of political discourse – China’s rise, India’s emergence as a geopolitical player, the growing roles of Brazil and South Africa.

But it seems we have not yet faced up properly to the implications. We can imagine sharing power, but we assume the bargain will be struck on our terms: that the emerging nations will be absorbed into the existing international institutions.

When we keep on promoting western values (which I hope we do) – preaching the virtues of the rule of law, pluralist politics and fundamental human rights, a liberal market system and global rules – we should face the fact that the west can no longer assume the global order will be remade in its own image.

„For more than two centuries, the US and Europe have exercised an effortless economic, political and cultural hegemony“, wrote a Financial Times columnist last week, which is certainly not suspect to anti-western feelings: „That era is ending.“

There are two major publications dealing with this situation – Fareed Zakaria’s „The Post-American World“ and Robert Kagan’s „The Return of History and the End of Dreams“. Both are not written as contributions to the foreign policy agendas of the McCain and Obama campaigns. But still they can be read as elaborations on two alternative worldviews that shape the respective foreign policy ideas of the candidates.

Fareed Zakaria maps a world which is characterized by what he calls „the rise of the rest“ – namely India and China, Russia and Brazil, but also many other medium sized powers on the world stage. I will not repeat this argument here, because it is widely known. But the consequences Zakaria draws from it are interesting: The west, he says, will no longer be able to dictate the terms of the world order, but he will still be able to lead. A different kind of leadership is required:

„Geopolitics is a struggle for influence“, says Zakaria: „As other nations become more active internationally, they will seek greater freedom of action. This necessarily means that America’s unimpeded influence will decline. But if the world that’s being created has more power centers, nearly all are invested in order, stability and progress. Rather than narrowly obsessing about our own short-term interests and interest groups, our chief priority should be to bring these rising forces into the global system, to integrate them so that they in turn broaden and deepen global economic, political, and cultural ties. If China, India, Russia, Brazil all feel that they have a stake in the existing global order, there will be less danger of war, depression, panics, and breakdowns. There will be lots of problems, crisis, and tensions, but they will occur against a backdrop of systemic stability. This benefits them, but also us. It’s the ultimate win-win.

To bring others into this world, the United States needs to make its own commitment to the system clear. So far, America has been able to have it both ways. It is the global rule-maker but doesn’t always play by the rules.“

Robert Kagan’s picture is in stark contrast: Kagan thinks the world is „back to normal again“, after a period of pipe dreams inspired by the fall of the Berlin wall and the end of communism. The ideas of a New World Order, of the End of History, of the historic march of liberal democracy have come to an end. Nationalism, Great Power rivalry for influence and resources and religious fanatcism are back to challenge the idea of a liberal democratic order.

Kagan sees Russia, China and Iran as examples of nations claiming their place under the sun. The enlightenment idea that democracy, open trade and the welfare of nations would make the power of nationalism and the thirst for recognition obsolete has been discredited in his view. We are facing once again the eternal appeal of power politics, national pride and newcomers yearning for respect.

This is the point at which Zakaria and Kagan meet: Both are responding to the ambitions of the non-western world. But Kagan believes that the conflicts of the coming years will fall into the cluster of our camp of liberal democracies facing another camp – of autocracies.

In contrast, Zakaria stresses that there will be no single overarching theme for many of the most urgent conflicts on the international agenda. The classic tools of unilateral foreign policy on the national level – like containment, boycotts or military intervention – cannot meet the challenges of climate change, financial crises, international terrorism or the fight against lethal viruses.

Secondly, America (and the West as a whole) finds itself in an increasingly competitive world – in terms of scientific inventiveness, cultural attraction, societal openness and political legitimacy. Practicing what you preach (in terms of human rights, interventionism, fiscal discipline, environmental protection) would be a good thing to start with.

Robert Kagan agrees with Zakaria about the limits of unilaterlism, but his consequences could not be more different: He thinks we should prepare for a bold new stance of the free world against the resurgent autocracies. He does not think that the defining criterium of the „West“ is cultural roots in the euro-atlantic sphere. Rather it is the commitment to political principles and values of liberla democracy. This is why India would be part of his club, and Russia not.

He calls for a „league of democracies“ to replace the ineffective UN security council, dysfunctional NATO or a G8 summit that has become a mere photo opportunity. Instead of integrating the rest into the existing institutions (and reforming them in the process), he wants to bypass these institutions and create a new one, based on common values of the democratic world. He lumps China, Russia and Iran together in the camp of „the other“, of „unfreedom“. India gets a visa for the liberal camp, because of its democratic system.

What’s wrong with this idea? It doesn’t look so bad at first sight.

Well, here’s the problem: By creating a „league of democracies“ you would implicitly contribute to the founding of a league of autocracies. Why would you want to do that? The interesting thing about the various shades of tyranny in today’s world is exactly this: that there is no overarching ideology to keep them together like in the time of communism. Instead of creating an enemy camp that we are up against together – we should be making use of the internal differences of the non-democracies or pseudo-democracies.

The Chinese have more economic power over the United States than Russia. With this power comes a much more vital interest in the west’s stability. There are very important domestic differences thta shape the foreign policies of both countries: The Russian and the Chinese government may both be autocratic. But they are very different in the way that the rulers depend on their peoples in terms of political legitimacy. The Russian rulers will face no problem until the oil and gas revenues drop below a certain margin, just like all the other petro-states of today. The legitimacy of Russia’s regime is actually very similar to the one of Dubai. Russia today faces the question, if it wants to be with the stupid and corrupt petrostates – or with the smart and not quite so corrupt petrostates.

The Chinese situation is very different, although the level of political unfreedom may be similar: The Chinese leaders are much more exposed to their population, because they depend on a willing an increasingly educated workforce. They have to deliver careers and better living conditions through intelligent navigation in the global market. Why lump these two systems together under one bold headline: autocracy! This effectively limits the western possibilities in dealing with them, and making use of their strength and weaknesses.

Let me finally get back to the current crisis and its foreign policy impact: the idea of a league of democracies, acting against or without regard for powers like China is itself a pipe dream! The Chinese stake in the american economy is much too big, and the Russian leverage in the European energy sector is much too big to make such a concept politically viable.

How will all this affect transatlantic affairs?

Firstly – it will become more and more difficult to fund the two major wars that we are fighting. The pressure for troop withdrawal from Iraq and Afghanistan is likely to mount when western societies begin to feel the full weight of the financial crisis. It is already very high. The US and the European Partners need to find a common response to this pressure.

Secondly – the cost of diplomatic unity with Russia and China vis à vis Iran will likely rise. Russia’s and China’s cooperation are vital for the diplomatic solution of the crisis. But western leaders are still voicing a very strong position about NATO expansion towards Ukraine and Georgia. My guess is that both these projects are not going to be realised anytime soon. Nobody is calling them off officially – but everybody knows that the calls to keep the accession process open are mere lip-service. Aggressive NATO expansion of the type we have seen in the last decade simply will not happen anymore.

The phase in which we could have it all – enlarging NATO, building a missile shield in Russia’s neighborhood, encouraging Kosovo to break away from Serbia, while at the same time expecting Russia’s help with the Iranian nuclear problem – is over.

Two weeks ago, the two former secretaries of state Henry Kissinger and George Shultz called for an end of the confrontational course with Russia. Nobody was paying attention, because the economic meltdown had sucked up all the air. But it is an important document. I quote: „Isolating Russia is not a sustainable long-range policy. It is neither feasible nor desirable to isolate a country spanning one-eighth of the earth’s surface, adjoining Europe, Asia and the Middle East, and possessing a stockpile of nuclear weapons comparable to that of the United States. … America must decide whether to deal with Russia as a possible strategic partner or as a threat to be combated by principles drawn from the Cold War.“

The same applies to the question of relations with China: Will we see a very strong and unified position of the West about tibetan independence, about human rights abuses or environmental concerns? I doubt it.

Most likely, we will see a new era of realism, of détente, or to use a very special German word: Entspannungspolitik.

A new era of détente can also bring new dangers: It was a disturbing characteristic of 70s and 80s détente that the dissidents of the Eastern Block were sometimes treated as a mere nuisance, disturbing peace and stability. This could happen again with the small baltic countries and some new member states and their fears about Russia. This could happen again to democracy avctivists in the Arab world or Tibet, if the West becomes overwhelmed by the rise of the rest. There is an inherent invitation to political-moral laziness in this perspective.

The multipolar world could be bad news for bloggers in Egypt, feminists in Iran or monks in Tibet. Some of the Realist would like to forget about the democracy advocates, the activists, the dissidents and the small countries with their haunted memories. They all threaten the stability that we once again have come to cherish after years of aggressive democracy promotion.

A backlash from Bush-style hubris to shere acceptance of the status quo would be just another disaster. The real question is, if we find a way of championing human rights, democracy and rule of law without self-righteousness and without false humility.

We need a new Entspannungspolitik, a new détente, outspoken and measured at the same time. This can only work as a common, transatlantic project. Divided we fall.