Stanley Fish, der berühmte Literaturwissenschaftler, hat sich in seinem Blog der Affäre um „The Jewel of Medina“ angenommen. (Mein Bericht hier.)

Fish widerspricht Salman Rushdie, der seinen eigenen Verlag Random House öffentlich bezichtigt hatte, durch den Rückzug des Romans über Mohammeds Lieblingsfrau Aischa „Zensur aus Angst“ geübt zu haben und einen „sehr schlechten Präzedenzfall geschaffen“ zu haben.

Fish weist nach, es habe sich nicht um Zensur gehandelt:

„It is also true, however, that Random House is free to publish or decline to publish whatever it likes, and its decision to do either has nothing whatsoever to do with the Western tradition of free speech or any other high-sounding abstraction.

Rushdie and the pious pundits think otherwise because they don’t quite understand what censorship is. Or, rather, they conflate the colloquial sense of the word with the sense it has in philosophical and legal contexts. In the colloquial sense, censorship occurs whenever we don’t say or write something because we fear adverse consequences, or because we feel that what we would like to say is inappropriate in the circumstances, or because we don’t want to hurt someone’s feelings. (This is often called self-censorship. I call it civilized behavior.)

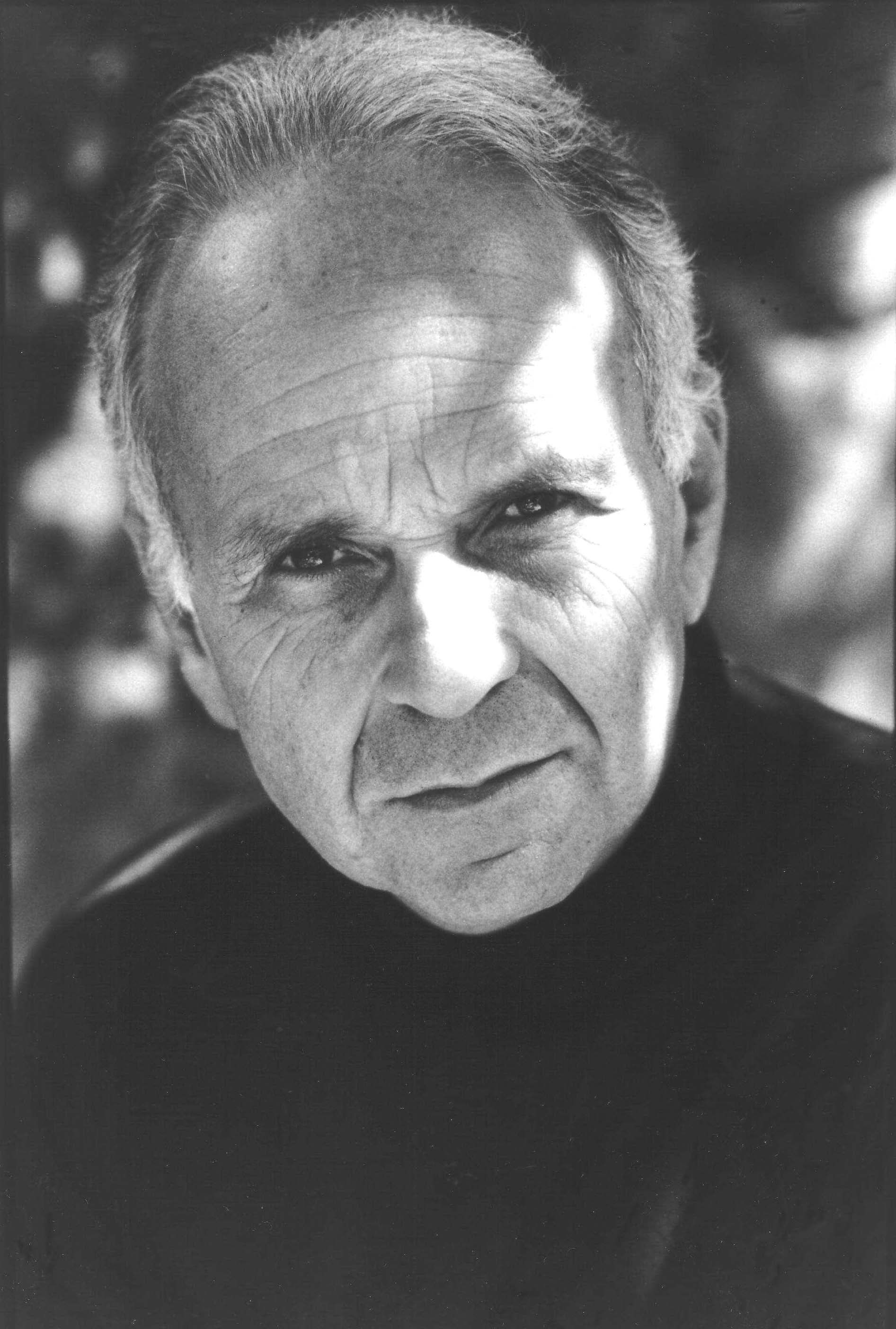

Stanley Fish

From the other direction, many think it censorship when an employee is disciplined or not promoted because of something he or she has said, when people are ejected from a public event because they are judged to be disrupting the proceedings, or when a newspaper declines to accept an advertisement, rejects an op-ed or a letter, or fails to report on something others think important. But if censorship is the proper name for all these actions, then censorship is what is being practiced most of the time and is in fact the norm rather than the (always suspect) exception.

But censorship is not the proper name; a better one would be judgment. We go through life adjusting our behavior to the protocols and imperatives of different situations, and often the adjustments involve deciding to refrain from saying something. …

But if none of these actions fit the definition of censorship, what does?

It is censorship when Germany and other countries criminalize the professing or publication of Holocaust denial. (I am not saying whether this is a good or a bad idea.) It is censorship when in some countries those who criticize the government are prosecuted and jailed. It was censorship when the United States Congress passed the Sedition Act of 1798, stipulating that anyone who writes with the intent to bring the president or Congress or the government “into contempt or disrepute” shall be “punished by a fine not exceeding two thousand dollars and by imprisonment not exceeding two years.” Key to these instances is the fact that (1) it is the government that is criminalizing expression and (2) that the restrictions are blanket ones. That is, they are not the time, manner, place restrictions that First Amendment doctrine traditionally allows; they apply across the board. You shall not speak or write about this, ever. That’s censorship.“

Kurz gesagt: Zensur im strengen Sinn liegt nur dann vor, wenn eine Regierung jedweden Ausdruck eines Sachverhalts per se verbietet.

Random House habe also sehr wohl das Recht zu veröffentlichen, was auch immer dem Verlag beliebt – und genauso, von einer Veröffentlichung Abstand zu nehmen, wenn etwa neue Gesichtspunkte den Verlag zum Umdenken über ein Projekt bewegen.

Mag sein.

Aber ist es vielleicht nicht beunruhigend, wenn ein Verlag das Buch bestellt, produziert und druckt – und erst zurückzieht, wenn „Berater warnen, seine Veröffentlichung könne Rassenkonflikte heraufbeschwören“ (consultants warned that its publication ‚could incite racial conflict‘)?

Vielleicht ist das nicht Zensur im strikten Sinn, aber es wie Fish einfach nur als „zivilisiertes Verhalten“ zu bezeichnen, scheint mir arge Schönfärberei.

Womöglich hat Fish Recht, vor dem Aufblasen dieser Episode zu einem „Showdown“ zu warnen. Aber leider ist es nicht die erste solche Episode. Ein großer Verlag fällt eine solche Entscheidung aus einem Klima der Angst – das ist das Thema.