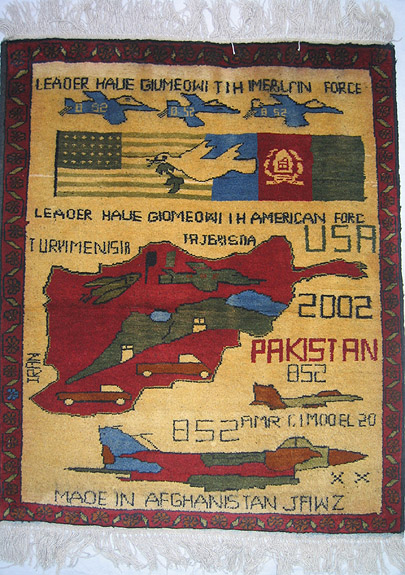

In Afghanistan gibt es diese Teppiche, die sich mit akuellen Geschehnissen beschäftigen. Dieser hier ist rätselhafter Weise überschrieben mit „Leader have come with American Force“ und handelt vom Krieg gegen den Terrorismus.

(Mehr hier.)

Andere Teppiche beschäftigen sich mit dem Abzug der Sowjets.

Und wenn man diese Teppiche anschaut, weht einen schon ein gewisser Defätismus an: Was werden die Weber für Bilder knüpfen, wenn wir eines Tages abziehen? Ob es wirklich noch 10 Jahre dauert, wie Peter Struck gestern in der Berliner Zeitung sagte? Die Debatte um den Sinn des Krieges in Afghanistan bekomt zusehends Fahrt. Hier der kritische Konservative Andrew Bacevich:

„What is it about Afghanistan, possessing next to nothing that the United States requires, that justifies such lavish attention? In Washington, this question goes not only unanswered but unasked. Among Democrats and Republicans alike, with few exceptions, Afghanistan’s importance is simply assumed—much the way fifty years ago otherwise intelligent people simply assumed that the United States had a vital interest in ensuring the survival of South Vietnam. As then, so today, the assumption does not stand up to even casual scrutiny.

…

Fixing Afghanistan is not only unnecessary, it’s also likely to prove impossible. Not for nothing has the place acquired the nickname Graveyard of Empires. Of course, Americans, insistent that the dominion over which they preside does not meet the definition of empire, evince little interest in how Brits, Russians, or other foreigners have fared in attempting to impose their will on the Afghans. As General David McKiernan, until just recently the U.S. commander in Afghanistan, put it, “There’s always an inclination to relate what we’re doing with previous nations,” adding, “I think that’s a very unhealthy comparison.” McKiernan was expressing a view common among the ranks of the political and military elite: We’re Americans. We’re different. Therefore, the experience of others does not apply.

Of course, Americans like McKiernan who reject as irrelevant the experience of others might at least be willing to contemplate the experience of the United States itself. Take the case of Iraq, now bizarrely trumpeted in some quarters as a “s

uccess” and even more bizarrely seen as offering a template for how to turn Afghanistan around.

Much has been made of the United States Army’s rediscovery of (and growing infatuation with) counterinsurgency doctrine, applied in Iraq beginning in late 2006 when President Bush announced his so-called surge and anointed General David Petraeus as the senior U.S. commander in Baghdad. Yet technique is no substitute for strategy. Violence in Iraq may be down, but evidence of the promised political reconciliation that the surge was intended to produce remains elusive. America’s Mesopotamian misadventure continues.

…

So the answer to the question of the hour—What should the United States do about Afghanistan?—comes down to this: A sense of realism and a sense of proportion should oblige us to take a minimalist approach. As with Uruguay or Fiji or Estonia or other countries where U.S. interests are limited, the United States should undertake to secure those interests at the lowest cost possible.

What might this mean in practice? General Petraeus, now commanding United States Central Command, recently commented that “the mission is to ensure that Afghanistan does not again become a sanctuary for Al Qaeda and other transnational extremists,” in effect “to deny them safe havens in which they can plan and train for such attacks.”

The mission statement is a sound one. The current approach to accomplishing the mission is not sound and, indeed, qualifies as counterproductive. Note that denying Al Qaeda safe havens in Pakistan hasn’t required U.S. forces to occupy the frontier regions of that country. Similarly, denying Al Qaeda safe havens in Afghanistan shouldn’t require military occupation by the United States and its allies.

It would be much better to let local authorities do the heavy lifting. Provided appropriate incentives, the tribal chiefs who actually run Afghanistan are best positioned to prevent terrorist networks from establishing a large-scale presence. As a backup, intensive surveillance complemented with precision punitive strikes (assuming we can manage to kill the right people) will suffice to disrupt Al Qaeda’s plans. Certainly, that approach offers a cheaper and more efficient alter-native to establishing a large-scale and long-term U.S. ground presence—which, as the U.S. campaigns in both Iraq and Afghanistan have demonstrated, has the unintended effect of handing jihadists a recruiting tool that they are quick to exploit.

In the immediate wake of 9/11, all the talk—much of it emanating from neoconservative quarters—was about achieving a “decisive victory” over terror. Weiter„Defätistische Gedanken beim Betrachten von Kriegsteppichen aus Afghanistan“