In der Herald Tribune stellt Adrian Pabst das Dialogangebot der 138 muslimischen Gelehrten, das hier schon mehrfach Thema war, in Frage.

Pabst hält es für oberflächlich und irreführend, wenn im dem Appell „A Common Word“ suggeriert werde, Gottesliebe und Nächstenliebe bei Muslimen und Christen laufe auf das Gleiche hinaus.

Pabst glaub, statt eines solchen „Dialogs“, der über die Unterschiede hinwegschaue, brauche man endlich eine angstfreie offene Debatte über die gravierenden Unterschiede in den beiden montheistischen Offenbarungen. Sonst kommen nur „höfliche Platitüden“ bei dem so genannten Dialog heraus.

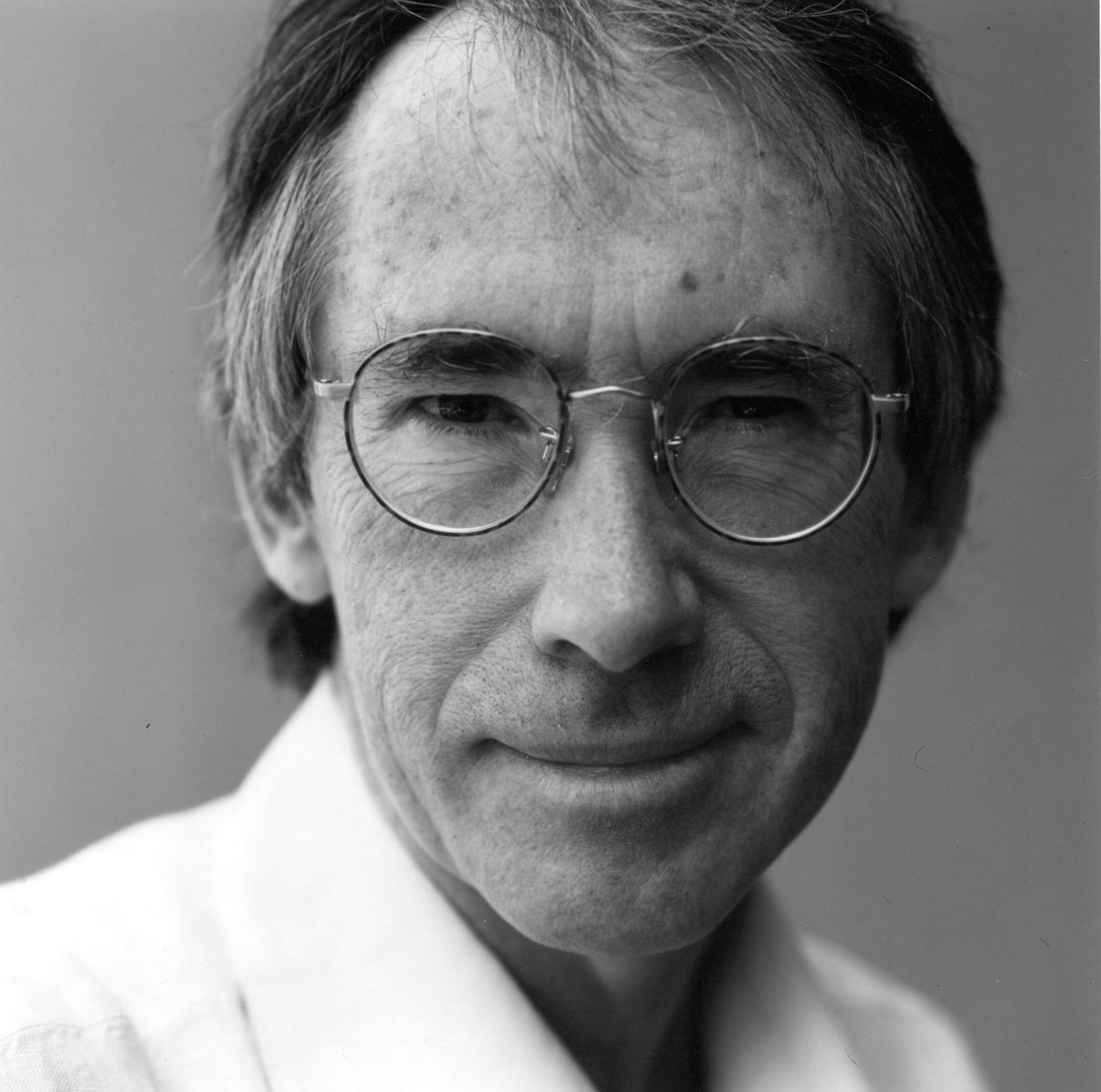

Adrian Pabst

Pabst stellt heraus, dass der christliche Gott ein „inkarniertes“ und beziehungsvolles Wesen sei: Die Dreifaltigkeit des einen Gottes, wie sie in den frühen christlichen Schriften dargestellt werde – Vater, Sohn und Heiliger Geist – sei nicht nur eine doktrinäre Marotte, sondern habe gravierende soziale und politische Folgen. Die Gleichheit der drei göttlichen Gestalten sei nämlich die Basis für die christliche Lehre von der Gleichheit unter den Menschen – jeder geschaffen als Abbild und in Ähnlichkeit des dreieinigen Gottes. Ein radikaler Egalitarismus sei darum im Kern des Christentums, der sich auch immer wieder gegen die Kirche und ihre Hierarchie richten könne.

Der muslimische Gott hingegen sei abstrakt und entrückt, körperlos und absolut – „kein Gott ausser Gott“, nichts ist ihm beigesellt. Die Offenbarung ist exklusiv an Mohammed ergangen, der Koran das wörtliche Wort Gottes, und wie es zwischen Gott und dem Menschen einen absoluten Unterschied gebe (der im Christentum durch Jesus aufgehoben wurde), so auch zwischen Gläubigen und Ungläubigen. Zwischen dem Politischen und der Religion hingegen gebe es eine notwendige Vermischung, da die islamische Offenbarung auch eine „Prämie auf territoriale Eroberung und Kontrolle“ beinhalte.

Zitat:

But to suggest, as the authors of „A Common Word“ do, that Muslims and Christians are united by the same two commandments which are most essential to their respective faith and practice – love of God and love of the neighbor – is theologically dubious and politically dangerous.

Theologically, this glosses over elementary differences between the Christian God and the Muslim God. The Christian God is a relational and incarnate God. Moreover, the New Testament and early Christian writings speak of God as a single Godhead with three equally divine persons – Father, Son and Holy Spirit.

This is not merely a doctrinal point, but one that has significant political and social implications. The equality of the three divine persons is the basis for equality among mankind – each and everyone is created in the image and likeness of the triune God.

As a result, Christianity calls for a radically egalitarian society beyond any divisions of race or class. The promise of universal equality and justice that is encapsulated in this conception of God thus provides Christians with a way to question and transform not only the norms of the prevailing political order but also the (frequently perverted) social practices of the Church.

By contrast, the Muslim God is disembodied and absolutely one: there is no god but God, He has no associate. This God is revealed exclusively to Muhammed, the messenger (or prophet), via the archangel Gabriel. As such, the Koran is the literal word of God and the final divine revelation first announced to the Hebrews and later to the Christians.

Again, this account of God has important consequences for politics and social relations. Islam does not simply posit absolute divisions between those who submit to its central creed and those who deny it; it also contains divine injunctions against apostates and unbelievers (though protecting the Jewish and Christian faithful).

Moreover, Islam’s radical monotheism tends to fuse the religious and the political sphere: It privileges absolute unitary authority over intermediary institutions and also puts a premium on territorial conquest and control, under the direct rule of God.

These (and other) differences imply that Christians and Muslims do not worship or believe in the same God; in consequence, across the two faiths, love of God and love of the neighbor invariably differ.

By ignoring these fundamental divergences, the authors of the open letter perpetuate myths about Christians and Muslims praying differently to the same God. Worse, they exhibit a simplistic theology of absolute, unmediated monotheism.

In this way, they unwittingly play into the hands of religious extremists on both sides who claim to have immediate, total and conclusive knowledge of divine will by faith alone.

The problem with all textual interpretations is that they are, by definition, particular and partly subjective. Without universal concepts and objective standards such as rationality, scholars differ from extremists merely in terms of their honorable intentions.

So the political danger of focusing Christian-Muslim dialogue on textual reading is that it neglects each faith’s theological specificities and the social implications; as such, this approach undermines the mutual understanding which it purports to offer but fails to deliver.

Christian and Muslims can no longer eschew the fundamental differences that distinguish their religions. The best hope for genuine peace and tolerance between Christianity and Islam is to have a proper theological engagement about the essence of God and the nature of peace and justice.